The Inuit (“the people” in the local language) moved into Northern Canada at the end of the last Ice Age, from Eastern Siberia to Alaska and then across Canada to Greenland. The Inuit were based mainly west and south-west of Hudson’s Bay. They were traditionally nomadic hunters. Their traditional art was small, mainly carved ivory and similar, representing animals, birds and fish, and also small toys to improve hand-eye co-ordination for hunters.

Europeans moved into their territory in the 16th Century, seeking whales and other resources, and trade started as the Inuit territory was traditionally short of metal and similar resources. One Inuit skill in demand was for art, so the Inuit learnt to produce carvings that appealed to their European and later Canadian traders.

The Canadian government thought in the 20th Century that the Inuit culture would die out, as primitive, and forced both settlement in towns and forced boarding schools, breaking up families and taking away the hunting and nomadic basis of the society.

In the 1950s onwards, people realised that there was a demand for Inuit art and carvings and encouraged the development of this market. Much of what is produced is recent and reflects Canadian and wider European tastes. Henrietta showed many exquisite carvings and prints. The style reflected older pieces, but also the demands of the market. For instance, much recent carving is in soapstone, which is easy to carve but very soft, so the style of carving has been altered at the request of the Canadian Postal Service as rounded pieces are easier to ship without damage.

Henrietta spoke very well; she is a new Arts Society lecturer, and indeed this was her first Arts Society talk. Everyone who listened was roused to find out more about this area, which was not well known to most TASH members.

Professor Robert Gurney

Dr Henrietta Hammant is a museum anthropologist with a love of the polar regions. She holds a BA in Archaeology and Anthropology from the University of Cambridge, where she completed a dissertation examining the interactions between humans and polar bears in Arctic Alaska. She then undertook an MSc in Visual, Material and Museum Anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she wrote her dissertation on the object biographies of a series of photographs held at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

Dr Henrietta Hammant is a museum anthropologist with a love of the polar regions. She holds a BA in Archaeology and Anthropology from the University of Cambridge, where she completed a dissertation examining the interactions between humans and polar bears in Arctic Alaska. She then undertook an MSc in Visual, Material and Museum Anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she wrote her dissertation on the object biographies of a series of photographs held at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

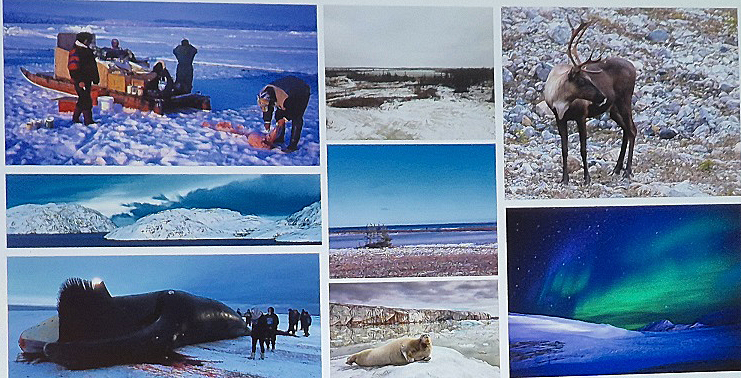

She has several years' experience working in museums in Canada and the UK, including the Itsanitaq Museum in Churchill, sub-Arctic Manitoba ('The Polar Bear Capital of the World') and, more recently, the Polar Museum at the Scott Polar Research Institute, part of the University of Cambridge. While at the Polar Museum she curated two temporary exhibitions, including the Institute's centenary year exhibition, which drew her south from her interest in the Arctic to the Antarctic, and the subject of her current research.

Dr Hammant has recently completed a PhD in the anthropology of heritage, studying the impact of museum practice on the interpretation of Antarctic explorers of the 'Heroic Age'.